Malte Bruns | Auto Body

Malte Bruns (*1984 in Bielefeld, lebt in Düsseldorf) studierte an der Staatlichen Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe und an der Akademie der Bildenden Künste München. An der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf schloss er 2014 sein Studium als Meisterschüler von Georg Herold ab.

2017 zeigte KIT – Kunst im Tunnel in Düsseldorf eine umfangreiche Einzelausstellung von Bruns. In Gruppenausstellungen war er u.a. an „Grim Tales“, 2017, Cassina Projects, New York, und „The One Minutes: The Pack – Impressions from OUR Family“, 2016, EYE Film Instituut Nederland, Amsterdam, beteiligt.2016 war er für den Nam June Paik Award nominiert.

In seiner ersten Einzelausstellung in der Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer zeigt der deutsche Künstler Malte Bruns neue bildhauerische Arbeiten, Fotografien und Videos, in denen er sich mit einem autarken Körper und dem Eigenleben menschlicher Gliedmaßen und Organe auseinandersetzt. Der Ausstellungstitel „Autobody“ ist doppeldeutig: Zunächst benennt er die Hülle eines Vehikels, dessen Karosserie das technische Innenleben umgibt und dieses nach Außen hin unsichtbar macht. Weiterhin referenziert „Autobody“ den „Körper für sich selbst“, der außerhalb des menschlichen Bewusstseins ein – mehr oder weniger deutlich sichtbares – automatisiertes Eigenleben führt.

Malte Bruns (*1984 in Bielefeld, lives in Düsseldorf) studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts Karlsruhe and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. He graduated as a „Meisterschüler“ of Georg Herold at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 2014. In 2017, KIT – Kunst im Tunnel showed Bruns’ works in a comprehensive solo exhibition. He participated in group exhibitions such as “Grim Tales“, 2017, Cassina Projects, New York, and “The One Minutes: The Pack – Impressions from OUR Family“, 2016, EYE Film Institute Netherlands, Amsterdam. He was shortlisted for the Nam June Paik Award in 2016.

In his first solo exhibition at Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer, the German artist Malte Bruns presents new sculptural works, photographs, and videos, dealing with the autarchic body and an independent existence of human limbs and organs. The title of the exhibition ‘Autobody' is ambiguous: initially, it signifies the shell of a vehicle, the outer bodywork that covers the technical inner workings and makes them invisible to the outside world. Furthermore, ‘Autobody' also refers to the ‘autonomous body', which leads to a - more or less visible - automatized life of its own, beyond the awareness of the human being.

-

Malte BrunsNatural Selection, 2018Inkjetprint, framed140 x 100 x 3 cm

Malte BrunsNatural Selection, 2018Inkjetprint, framed140 x 100 x 3 cm

55 1/8 x 39 3/8 x 1 1/8 in -

Malte BrunsHoly Maceroni, 2018PUR, metal28 x 75 x 31 cm

Malte BrunsHoly Maceroni, 2018PUR, metal28 x 75 x 31 cm

11 1/8 x 29 1/2 x 12 1/4 in -

Malte BrunsJoint Venture, 2018PUR, platinum silicone, platinum siliconefoam, polyethylene thread20 x 11 x 15 cm

Malte BrunsJoint Venture, 2018PUR, platinum silicone, platinum siliconefoam, polyethylene thread20 x 11 x 15 cm

7 7/8 x 4 3/8 x 5 7/8 in -

Malte BrunsMerry Mary, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum sillicone, laquer, styrofoam, cardboard60 x 39 x 26 cm

Malte BrunsMerry Mary, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum sillicone, laquer, styrofoam, cardboard60 x 39 x 26 cm

23 5/8 x 15 3/8 x 10 1/4 in -

Malte BrunsMoneypenny, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum silicone, polyester, steel, polyethyle133.5 x 25 x 37.5 cm

Malte BrunsMoneypenny, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum silicone, polyester, steel, polyethyle133.5 x 25 x 37.5 cm

52 1/2 x 9 7/8 x 14 3/4 in -

Malte BrunsNight Fever, 2018PUR, styrofoam, polyester, metal, epoxy, platinum silicone, laquer70 x 32 x 32 cm

Malte BrunsNight Fever, 2018PUR, styrofoam, polyester, metal, epoxy, platinum silicone, laquer70 x 32 x 32 cm

27 1/2 x 12 5/8 x 12 5/8 in -

Malte BrunsTorso, 2018PUR, platinum silicone, platinum silicone foam, metal, epoxy42 x 65 x 38 cm

Malte BrunsTorso, 2018PUR, platinum silicone, platinum silicone foam, metal, epoxy42 x 65 x 38 cm

16 1/2 x 25 5/8 x 15 in -

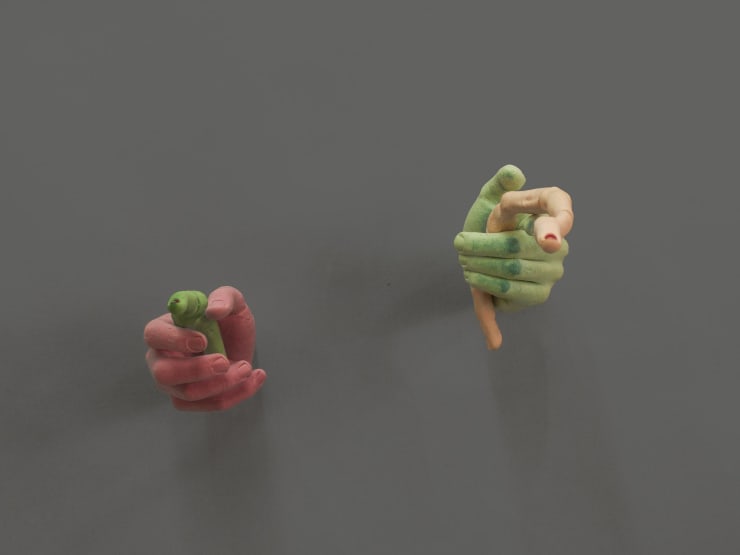

Malte BrunsWeapons of choice, 2018PUR, nail polish11 x 12 x 27 cm

Malte BrunsWeapons of choice, 2018PUR, nail polish11 x 12 x 27 cm

4 3/8 x 4 3/4 x 10 5/8 in

&

10 x 15 x 36 cm

4 x 5 7/8 x 14 1/8 in -

Malte BrunsGhostfinger, 2018PUR, wood, laquer164 x 56 x 50 cm

Malte BrunsGhostfinger, 2018PUR, wood, laquer164 x 56 x 50 cm

64 5/8 x 22 1/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Malte BrunsHow I met your mother, 2018Inkjet on dibond with custom epoxy frame

Malte BrunsHow I met your mother, 2018Inkjet on dibond with custom epoxy frame

Edition of 3, plus 1 AP104 x 74 x 5 cm

41 x 29 1/8 x 2 in -

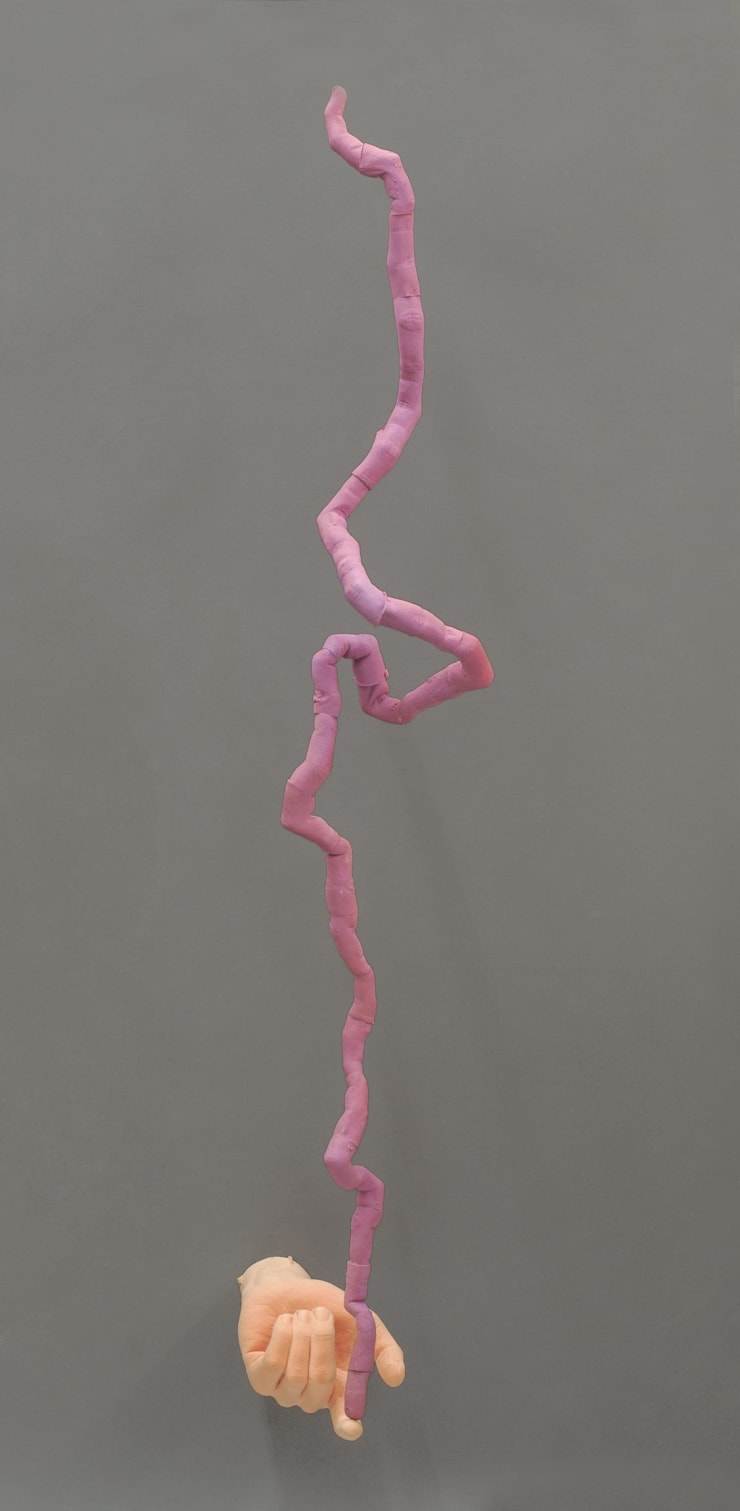

Malte BrunsSkywalker, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum silicone, polyester, steel, polyethyle153 x 37 x 32 cm

Malte BrunsSkywalker, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum silicone, polyester, steel, polyethyle153 x 37 x 32 cm

60 1/4 x 14 5/8 x 12 5/8 in -

Malte BrunsUps' n downs III, 2018PUR, metal15 x 102 x 26 cm

Malte BrunsUps' n downs III, 2018PUR, metal15 x 102 x 26 cm

5 7/8 x 40 1/8 x 10 1/4 in -

Malte BrunsWhat goes around comes around, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum silicone, polyester, steel, polytehyle121 x 64 x 49 cm

Malte BrunsWhat goes around comes around, 2018Epoxy resin, platinum silicone, polyester, steel, polytehyle121 x 64 x 49 cm

47 5/8 x 25 1/4 x 19 1/4 in

Malte Bruns (*1984 in Bielefeld, lebt in Düsseldorf) studierte an der Staatlichen Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe und an der Akademie der Bildenden Künste München. An der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf schloss er 2014 sein Studium als Meisterschüler von Georg Herold ab.

2017 zeigte KIT – Kunst im Tunnel in Düsseldorf eine umfangreiche Einzelausstellung von Bruns. In Gruppenausstellungen war er u.a. an „Grim Tales“, 2017, Cassina Projects, New York, und „The One Minutes: The Pack – Impressions from OUR Family“, 2016, EYE Film Instituut Nederland, Amsterdam, beteiligt.2016 war er für den Nam June Paik Award nominiert.

In seiner ersten Einzelausstellung in der Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer zeigt der deutsche Künstler Malte Bruns neue bildhauerische Arbeiten, Fotografien und Videos, in denen er sich mit einem autarken Körper und dem Eigenleben menschlicher Gliedmaßen und Organe auseinandersetzt. Der Ausstellungstitel „Autobody“ ist doppeldeutig: Zunächst benennt er die Hülle eines Vehikels, dessen Karosserie das technische Innenleben umgibt und dieses nach Außen hin unsichtbar macht. Weiterhin referenziert „Autobody“ den „Körper für sich selbst“, der außerhalb des menschlichen Bewusstseins ein – mehr oder weniger deutlich sichtbares – automatisiertes Eigenleben führt.

Die „body parts“ von Malte Bruns entstehen als Abformungen der eigenen Gliedmaßen des Künstlers in Kunststoffen, die dann mit grellen Farben versehen und miteinander kombiniert bzw. erweitert werden. So ergeben sich groteske Gestalten, die sowohl an die Errungenschaften der Gentechnik – etwa die Implantation eines menschlichen Ohrs einer Maus (Vacanti-Maus) – erinnern lassen als auch auf die Erzeugung neuartiger und ungewöhnlicher Wahrnehmungserfahrungen durch die Kombination disparater Gegenstände, wie sie als künstlerische Strategie seit dem Surrealismus zu finden sind, verweisen.

Es ist nicht der versehrte Mensch, der bei Bruns im Mittelpunkt steht, sondern die (vermeintliche) Erweiterung des Menschen und seiner Fähigkeiten durch Technologie. Die Bezüge seiner Arbeiten zur Prothesenindustrie treten zwar deutlich hervor, dennoch geht es dem Künstler nicht um die Offenlegung und Verhandlung beschädigter Bewegungsapparate. Vielmehr nimmt er in humorvoller Weise Bezug auf die Tendenzen in der Medizin, Genetik oder Robotik, den menschlichen Körper bionisch zu optimieren, diesem übermenschliche Kräfte zu verleihen.

Gerade die Sehnsucht des Menschen, zu erschaffen, einen Schöpfungsakt zu vollziehen, um sich selbst zu verbessern und die eigene Natur so besser verstehen zu können, wird von Bruns ironisch konterkariert. Der künstlerische Schöpfungsakt führt bei ihm ins Parodistische und Abstrakte. Historisch gehen Bestrebungen der Erzeugung übermenschlicher Fähigkeiten und Experimente in der Magie oder im Okkultismus voraus, auf die sich Bruns etwa in der nach dem gleichnamigen Zauber- und Entfesselungskünstler „Houdini“ benannten Arbeit mit einem Augenzwinkern bezieht. Houdinis Zauberei war Illusion, dennoch war er für Generationen von AmerikanerInnen ein Idol und hatte das Image des unbesiegbaren Supermenschen.

Zentrale Referenzen für seine Arbeiten findet Bruns in der Literatur, etwa in E.T.A. Hofmanns automatischer Puppe „Olympia“, aber vor allem in Hollywood- und Trashfilmen, wie Steve Barrons „Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles“ von 1990, einem Film, in dem Jim Hensons Effektstudio Creature Shop sich für die Kostüme verantwortlich zeichnete, oder dem in selben Jahr veröffentlichten „Batman“-Film von Tim Burton mit Jack Nicholson als Bösewicht Joker. Gerade in den Monstern dieser und ähnlicher Filme, deren fantastischen Helden und abstoßenden Schurken, findet der Künstler die Quellen für seine absurden Gestalten.

Mit einer „Ästhetik des Handgemachten“, wie sie aus den Requisitenstudios Hollywoods des letzten Jahrhunderts bekannt ist, kontrastieren Bruns‘ Arbeiten die Fassadenhaftigkeit und Glätte der Designs, die technologische Produktionen heute kennzeichnen. Die Ausführung seiner Plastiken übernimmt Bruns selbst in seinem Studio, zeitweilig mit Unterstützung einer Assistenz. Der Atelierboden dort wird zuweilen Teil der künstlerischen Arbeit: Bruns formt das Bodensegment, auf dem die jeweilige Arbeit produziert wurde, ab und überträgt so dessen Strukturen und Abnutzungserscheinungen auf die Standfläche seiner Plastik.

Malte Bruns treibt ein schelmisches Spiel mit Ekel und Abscheu. Den Höhepunkt des Abjekten (lat. „abjectus“: nachlässig, in höchstem Maße niederträchtig, ekelerregend) sieht die Literaturwissenschaftlerin Julia Kristeva im Kadaver, dem „gefallenen Objekt“. Bruns‘ Körperteile scheinen sich allerdings dem Verwesungsprozess zu widersetzen, scheinen ein unkontrollierbares Eigenleben aufzuweisen, das jenseits nachvollziehbarer und zielgerichteter Handlungsabläufe liegt – Reiz und Regung bleiben in ihnen allzeit vorhanden.

Text: Jürgen Dehm

Malte Bruns (*1984 in Bielefeld, lives in Düsseldorf) studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts Karlsruhe and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. He graduated as a „Meisterschüler“ of Georg Herold at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 2014. In 2017, KIT – Kunst im Tunnel showed Bruns’ works in a comprehensive solo exhibition. He participated in group exhibitions such as “Grim Tales“, 2017, Cassina Projects, New York, and “The One Minutes: The Pack – Impressions from OUR Family“, 2016, EYE Film Institute Netherlands, Amsterdam. He was shortlisted for the Nam June Paik Award in 2016.

In his first solo exhibition at Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer, the German artist Malte Bruns presents new sculptural works, photographs, and videos, dealing with the autarchic body and an independent existence of human limbs and organs. The title of the exhibition ‘Autobody' is ambiguous: initially, it signifies the shell of a vehicle, the outer bodywork that covers the technical inner workings and makes them invisible to the outside world. Furthermore, ‘Autobody' also refers to the ‘autonomous body', which leads to a - more or less visible - automatized life of its own, beyond the awareness of the human being.

Malte Bruns’ ‘body parts’ are created from the casts of the artist’s own limbs in synthetic materials which are subsequently luridly coloured and combined with one another, respectively extended. Thus, grotesque figures occur that remind of the achievements of genetic engineering - such as, for instance, the implantation of a human ear to a mouse (Vacanti mouse) - as well as referring to the creation of novel and unusual perceptual experiences by way of combining disparate objects - an artistic strategy that has existed since Surrealism.

The disabled human is not the focus of Bruns' work, but rather the (supposed) enhancement of the human being and their abilities through technology. The associations with the prosthetic industry are clearly evident, still, the artist is not concerned with disclosing or dealing with an impaired locomotory system. He rather refers in a humorous manner to the tendencies of medicine, robotics, and genetics to optimize the human body bionically. To equip it with superhuman powers. The human aspiration to bring something into existence, to carry out the act of creation, in order to improve oneself whilst also gaining a better understanding of one's own nature, is ironically countered by Bruns. The artistic act of creation turns into parody and abstraction. Historically, efforts to generate superhuman abilities were preceded by experiments within the areas of magic and the occultism, which Bruns alludes to - not entirely without a sense of humour - in his work entitled ‘Houdini’. Houdini’s magic was an illusion, still, he was an idol for generations of Americans and had the aura of an invincible superhuman.

Malte Bruns finds the central reference points for his work in literature, for instance, E.T.A. Hofmann's' automated doll ‘Olympia.' However many more points of reference come from the Hollywood and trash movies of the 1980s and 1990s. Films such as Steve Barron's ‘Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ from 1990, the costume of which had been created by Jim Henson’s special effect studio Creature Shop, or the ‘Batman’-movie by Tim Burton that was released in the same year and featured Jack Nicholson as the supervillain ‘the Joker’. Especially the monsters of these (or similar) movies, their fantastic heroes and repellent villains, constitute the sources for the artist’s absurd creatures. With their ‘handmade’ aesthetic, familiar from the prop rooms of last century’s Hollywood, Bruns’ works contrast the polished facades and the smooth surfaces featured in today’s technological productions. Malte Bruns’ sculptures are executed by himself, in his studio, at times supported by an assistant. Occasionally the studio floor becomes part of the artistic work: Bruns takes a cast of the floor segments the respective work was produced on and thus transfers the structures and the signs of wear onto the pedestal of his sculpture.

Malte Bruns plays mischievously with disgust and revulsion. For the literary scholar Julia Kristeva the cadaver, the ‘fallen object’, is the climax of abjectness (lat. „abjectus”: low, sordid, vile). Bruns’ body parts appear to resist decay, appear to have an uncontrollable life of their own, beyond comprehensible and goal orientated courses of action, in which stimulus and motion remain perpetually present.

Text: Jürgen Dehm