Richie Culver & Hannah Perry | Body Shop

Past exhibition

Overview

A Vauxhall Corsa on the M62, somewhere between Chester and Hull

On the work of Richie Culver and Hannah Perry by Adam Carr

Prior to being invited to write this text, I had often considered the mutual and partnered tendencies of Richie Culver and Hannah Perry’s work, not least for their time spent in my hometown of Chester – Perry was born in the city and Culver had spent time there while living with his sister.

It is hardly news that artists who work in a particular region or location share interests and that these imprints have been made known in the shape of conceptual and formal similarities, or at least via attitudes to working. Artists’ whereabouts and the location driven context that forms a practice have, of course, spawned many isms and moments in art history and can come to characterise and be emblematic of a particular way of working. Although it might be a place of inspiration, Chester is not, however, a capital city and in this way shares a different history therefore with artistic characteristics aligned with, for example, London, Paris, New York, or Los Angeles, and so on. Yet surprisingly for its relatively small size and its sheer lack of contemporary art presentation – there is no known art institution – Chester has delivered several contemporary artists known internationally, Ryan Gander, Jesse Wine, and Richard Woods among them. While both artists had spent time in the city, Culver’s upbringing in Hull is equally pertinent to the overlaps that occur between the two artist’s work. Although regionalism could be seen as acknowledgment in both artists’ works, it is rather a reactionary push against normative codes of social, political and other systems that characterise a way of behaving that could be considered in many ways as a meeting point for their practices.

Though Culver and Perry’s work grapples both with and within the confines of their upbringings, equally is a desire to speak urgently to much a larger context, one that submits the deeply personal to the universal. A will to speak further afield is perhaps a consequence of their upbringings in working class households which have, in turn, speared a yearning for elsewhere, for something other. Their practices are, in part, an acknowledgment of other artists and cognizant of how their work could play an alternative role in a history, or histories, of material consideration and subject matter, as well as presentation and delivery. Beyond such affinities is a shared arena of an intense commitment to aural concerns, often through working with sound but most notably through the deployment of tangible materials. Many of Culver’s work could recall lyrics, while his sound releases in form of albums and eps are as much part of his practice than his paintings. Perry’s work often makes use of sound, or more specifically soundwaves, and mines its ability to provide context for a set of largely visual and sculptural aspects.

Works

-

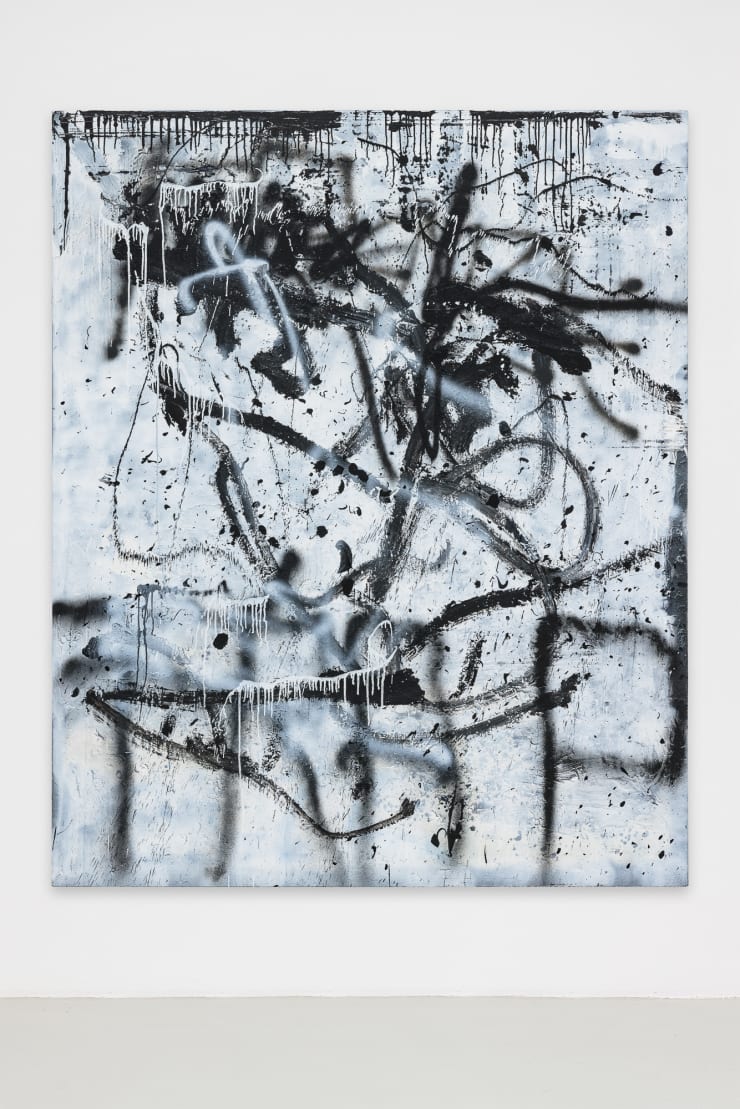

Richie CulverNice Nights, 2023Oil, household paint, lacquer, acrylic, gel, glue220 x 180 cm

Richie CulverNice Nights, 2023Oil, household paint, lacquer, acrylic, gel, glue220 x 180 cm

86 5/8 x 70 7/8 in -

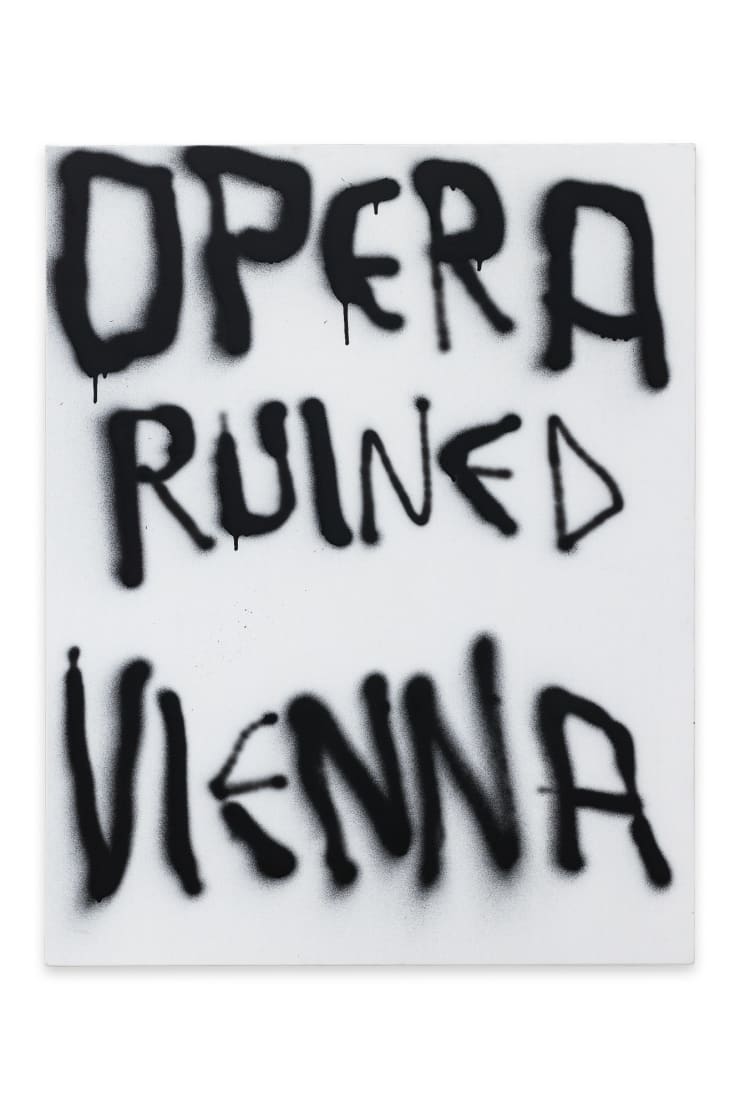

Richie CulverOpera runied Vienna, 2023Oil and lacquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

Richie CulverOpera runied Vienna, 2023Oil and lacquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in -

Richie CulverNice Try, 2023Oil, household paint, lacquer, acrylic, gel, glue220 x 180 cm

Richie CulverNice Try, 2023Oil, household paint, lacquer, acrylic, gel, glue220 x 180 cm

86 5/8 x 70 7/8 in -

Hannah PerryOn the Bonnet (two), 2023Aluminium, autobody wrap, acrylic paint95 x 80 x 15 cm

Hannah PerryOn the Bonnet (two), 2023Aluminium, autobody wrap, acrylic paint95 x 80 x 15 cm

37 3/8 x 31 1/2 x 5 7/8 in -

Hannah Perry, Crude Oil, 2023

Hannah Perry, Crude Oil, 2023 -

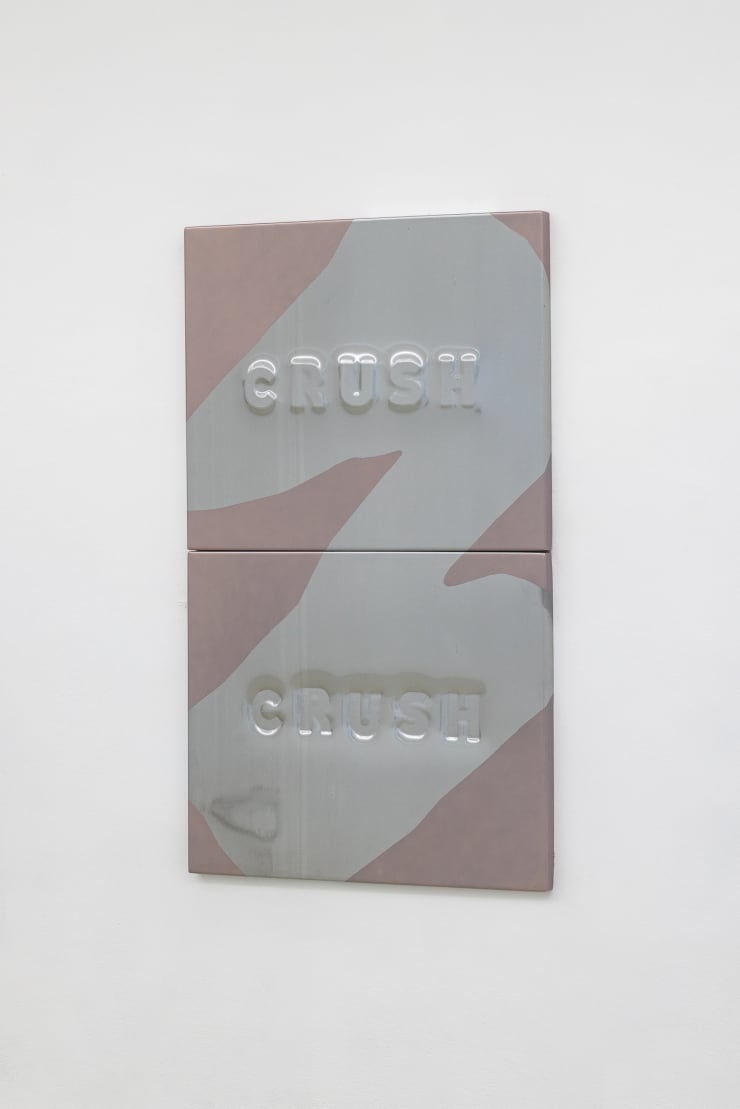

Hannah PerryCrushed on you /Crushed on me, 2023Aluminium, autobody paint2 pieces

Hannah PerryCrushed on you /Crushed on me, 2023Aluminium, autobody paint2 pieces

each 95 x 80 x 5 cm

37 3/8 x 31 1/2 x 2 in -

Richie CulverI stole your style it's mine now end of story, 2023Oil on lacquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

Richie CulverI stole your style it's mine now end of story, 2023Oil on lacquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in -

Richie CulverI do not need a studio and I do not need ideas, 2023Oil and lacquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

Richie CulverI do not need a studio and I do not need ideas, 2023Oil and lacquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in -

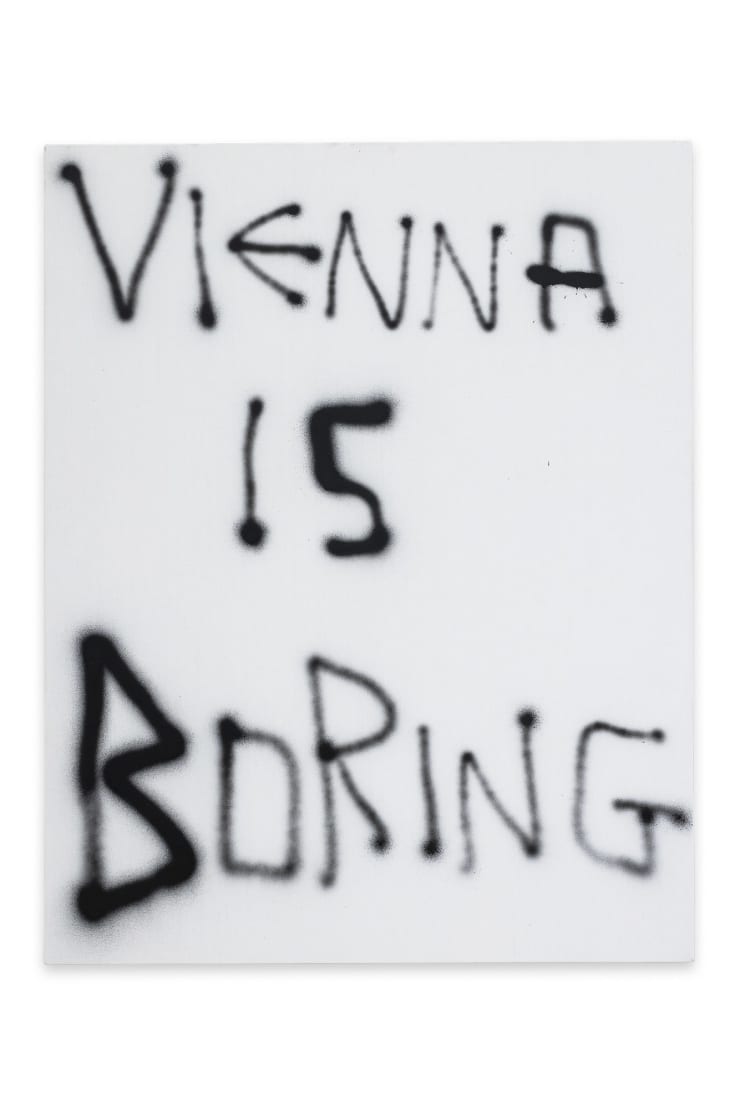

Richie CulverVienna is Boring, 2023Oil and laquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

Richie CulverVienna is Boring, 2023Oil and laquer on canvas100 x 80 cm

39 3/8 x 31 1/2 in -

Hannah PerryLoud Voices, 2023Steel150 x 100 x 30 cm

Hannah PerryLoud Voices, 2023Steel150 x 100 x 30 cm

59 x 39 3/8 x 11 3/4 in -

Hannah PerryOn the Bonnet (curvy), 2023Aluminium, Autobody wrap, acrylic paint95 x 80 x 15 cm

Hannah PerryOn the Bonnet (curvy), 2023Aluminium, Autobody wrap, acrylic paint95 x 80 x 15 cm

37 3/8 x 31 1/2 x 5 7/8 in -

Hannah PerryOn the Bonnet (swish), 2023Aluminium, Autobody wrap, acrylic paint95 x 80 x 15 cm

Hannah PerryOn the Bonnet (swish), 2023Aluminium, Autobody wrap, acrylic paint95 x 80 x 15 cm

37 3/8 x 31 1/2 x 5 7/8 in

Press release

A Vauxhall Corsa on the M62, somewhere between Chester and Hull

On the work of Richie Culver and Hannah Perry by Adam Carr

Prior to being invited to write this text, I had often considered the mutual and partnered tendencies of Richie Culver and Hannah Perry’s work, not least for their time spent in my hometown of Chester – Perry was born in the city and Culver had spent time there while living with his sister.

It is hardly news that artists who work in a particular region or location share interests and that these imprints have been made known in the shape of conceptual and formal similarities, or at least via attitudes to working. Artists’ whereabouts and the location driven context that forms a practice have, of course, spawned many isms and moments in art history and can come to characterise and be emblematic of a particular way of working. Although it might be a place of inspiration, Chester is not, however, a capital city and in this way shares a different history therefore with artistic characteristics aligned with, for example, London, Paris, New York, or Los Angeles, and so on. Yet surprisingly for its relatively small size and its sheer lack of contemporary art presentation – there is no known art institution – Chester has delivered several contemporary artists known internationally, Ryan Gander, Jesse Wine, and Richard Woods among them. While both artists had spent time in the city, Culver’s upbringing in Hull is equally pertinent to the overlaps that occur between the two artist’s work. Although regionalism could be seen as acknowledgment in both artists’ works, it is rather a reactionary push against normative codes of social, political and other systems that characterise a way of behaving that could be considered in many ways as a meeting point for their practices.

Though Culver and Perry’s work grapples both with and within the confines of their upbringings, equally is a desire to speak urgently to much a larger context, one that submits the deeply personal to the universal. A will to speak further afield is perhaps a consequence of their upbringings in working class households which have, in turn, speared a yearning for elsewhere, for something other. Their practices are, in part, an acknowledgment of other artists and cognizant of how their work could play an alternative role in a history, or histories, of material consideration and subject matter, as well as presentation and delivery. Beyond such affinities is a shared arena of an intense commitment to aural concerns, often through working with sound but most notably through the deployment of tangible materials. Many of Culver’s work could recall lyrics, while his sound releases in form of albums and eps are as much part of his practice than his paintings. Perry’s work often makes use of sound, or more specifically soundwaves, and mines its ability to provide context for a set of largely visual and sculptural aspects.

While not instantly apparent, upon closer examination, is a describable sense that the artists’ upbringings had been spent listening to a near exact soundtrack. Their sonic pursuits, or rather the type of sound that reverberates through their work, could be seen to be akin to several artists who likewise have been influenced by the near identical period of UK club culture – Mark Leckey, Oliver Payne and Nick Relph, and Simeon Barclay included, and from across the water Tony Cokes. The desire for emancipation, the type associated with from regional upbringings, and the longing to be part of a larger community, is a fundamental aspect and key to the understanding of both artist’s work.

Take, for example, Give Us A Little Smile (2011) and Wonderful While It Lasts (2012), a set of earlier work video works by Perry. Both films contain found footage and sampled self-shot imagery overlayed with various sound bites that range from spoken word to music. The audio becomes a structure for editing and overall visual presentation and vice versa, enveloping the viewer in a movement of sound and images where the two oscillate in a way that they become one and one another. Several cues point to the euphoria so often associated with club culture and how sound can shape and influence the body and its associations with identity, enabled by a wide number of events of this short though ever glowing era.

Perry’s recent sculptural assemblages, appearing in a set of installations, have placed sound as a visual element through revealing yet veiling it. No Tracksuits, No Trainers (2023) uses metal sheeting where projected sound waves come to vibrate and distort the material with relentless vigour. This amalgamation of sound and vision typifies Perry’s approach, where material gives form to sound and sound charges and alters form. Importantly, her use of arguably heavy materials and the physically robust connote industrial fabrication and this is by no accident – her immediate family, her brother and uncle, were welders. Littered with biographical and gendered centric references – the repeated presence of cars, clothing, and subjects – her work unfolds discussions about identity and investigates the complexity of the body. It is though the ghostly presence of Richard Serra and Donald Judd, along with other masculine figures of the highly polished and the industrially produced, have been transmitted through fragments from a far yet strangely connected lineage.

Culver’s work equally deals with cultural memory in relation to social class. More specifically, much of his work, as with Perry’s, examines the context of his own biography while acknowledging how this otherwise limited understanding fares with a more global purview. A most obvious case is an early series of photo essays that record his family history through a set of photographs interlaced with emotive texts. Works that immediately followed thereafter continued making use of at hand material, embraced mostly for its ease of use. Yet although the modest and earnest beginnings of his practice have been expressed by the artist in the form of interviews and texts, his work belies those conditions, which in fact look and feel incredibly conscious, erudite even, regarding the potential conversations they enter with art history.

Culver’s array of text-based paintings recalls painterly laziness, the type so often aligned with the school of bad painting – Kippenberger, Messe and Richter – and the cool and calm yet rapid and expressive gestures as found in the work of Christopher Wool and Micheal Krebber. His paintings record a history, pronouncing a process of their own making, and we can see several layers of perhaps abandoned and half-forgotten ideas scattered through them. Underlaying fragments are often overlayed with texts, and more recent works has seen messages placed at the centre and away from accompanying elements seen in earlier paintings. The paintings’ texts are always a result of a process of fast paced mark making, but these associations with speed and the fleeting are offset by the actual messages they contain, which are highly concentrated in their observation, addressing large and weighty concepts of our very existence. While Culver’s paintings might well feedback the medium’s history, their unapologetic musings on our lived reality – suggesting our attachment to screens and the incessant broadcast of images and information – speaks to a more present reality. Such sentiments are not exclusively bound to the use of painting and his performances have ushered an interdisciplinary approach, engaging audiences live, be it performing among the paintings in a gallery setting, or, as in a most recent delivery, in a fairground in Hull at the centre of the Waltzers.

Perry’s and Culver’s practices express sorrow, grief, and loss, but with those more optimistic ideals such as love, communication, and world building. With the origins of their practices set up apart by just a few miles one wonders if there was something in the waters that was the cause for the overlapping type of emotional conceptualism that underpins their work. Considering such set of concerns at stake in both artists’ work, it would not be farfetched to read them through the lens of Romanticism and its much-associated history with the Pre-Raphaelites era. Equally at home could be the recent press of issues of wellbeing, and to the effect of the often-unsolicited barrage of information in the social media age, beginning to be unravelled in contemporary production and inferred in the work of Carolyn Lazard, SoiL Thornton, or Martine Syms.

However, Perry’s and Culver’s works are a type of collective but personally endured history that makes it feel as though any associative art historical precedents are a temporary domain rather than a permanent fixture. Although perhaps not possibly without their lived history and particular set of circumstances, their work is performed both in the present and of the present and comes to wrestle with notions of identity, self, and expectations that we all, in various ways, must come to endure.

Installation Views

-

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023 -

Richie CulverInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023

Richie CulverInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023 -

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023 -

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023 -

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023 -

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023

Richie Culver & Hannah PerryInstallation View - Body Shop, 2023