Frauke Dannert | Folie [fɔli]

Frauke Dannert (b.1979 in Herdecke, Germany) studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and at Goldsmiths, University of London. In her works on paper as well as in her spatial installations, she follows the principles of collage. In 2016 the Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf and the Kunstmuseum Luzern both hosted a solo exhibition of her works. Additional solo exhibitions at the Kunstmuseum Bonn and the Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig are following in 2018. Currently, Frauke Dannert holds the Dorothea-Erxleben scholarship and teaches at the Braunschweig University of Arts. She lives and works in Cologne.

In her second solo exhibition at Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer, Frauke Dannert transfers her constructional and analytical strategies of collage from architecture to plant life. The title ‘folie’—the French term for a formally thought through, but otherwise useless building in garden architecture—refers, as regards content, to Dannert’s emblematic architectural collages. Phonetically the term simultaneously adds new clusters of visual motifs to her work: works on paper, photographs and a mural are dedicated to elements from the field of botany, such as the leaves (ital.: foglia / fr.: feuille) of a tree or a plant.

-

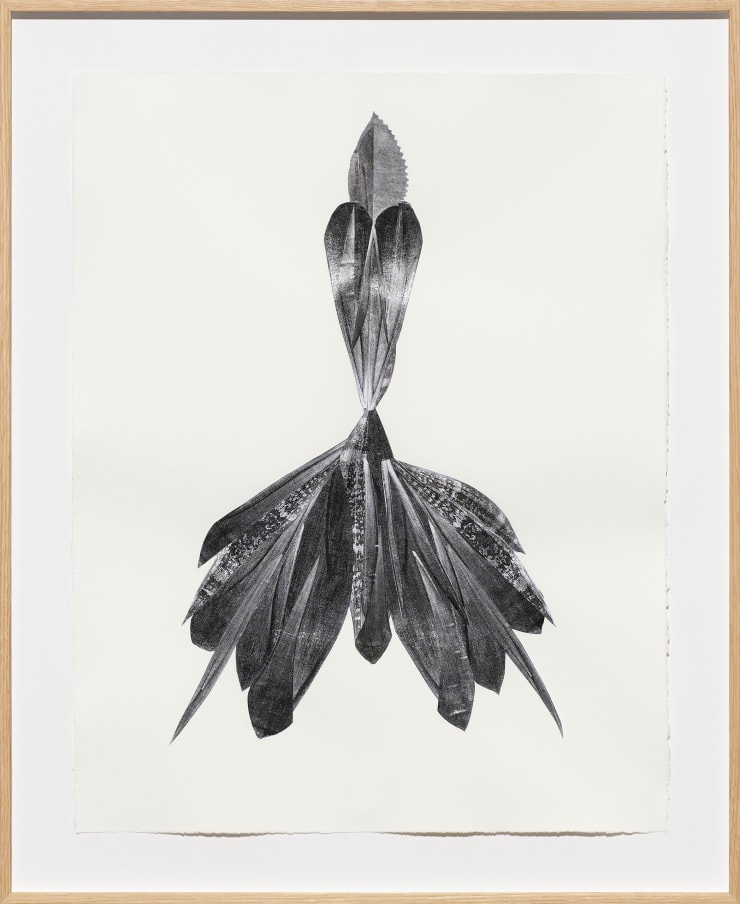

Frauke DannertFolie, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertFolie, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertFountain, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertFountain, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertFrucht, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

Frauke DannertFrucht, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in -

Frauke DannertGloriette, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertGloriette, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertHahn, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertHahn, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertHortus, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertHortus, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertKlee, 2017Paper Collage29.5 x 21.5 cm

Frauke DannertKlee, 2017Paper Collage29.5 x 21.5 cm

11 5/8 x 8 1/2 in -

Frauke DannertOhne Titel, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

Frauke DannertOhne Titel, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in -

Frauke DannertOhne Titel, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

Frauke DannertOhne Titel, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in -

Frauke DannertOrangerie, 20176 x Multiple exposure photography, hand print on baryta paper9 x 9 cmEdition 2 of 3

Frauke DannertOrangerie, 20176 x Multiple exposure photography, hand print on baryta paper9 x 9 cmEdition 2 of 3 -

Frauke DannertPalisade , 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertPalisade , 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertPatio, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

Frauke DannertPatio, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in -

Frauke DannertPavillon, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertPavillon, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertPagode, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

Frauke DannertPagode, 2018Paper Collage65 x 50 cm

25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in -

Frauke DannertZaunkönig, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

Frauke DannertZaunkönig, 2018Paper Collage29 x 21 cm

11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in

FRAUKE DANNERT folie [fɔli]

Frauke Dannert (b.1979 in Herdecke, Germany) studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and at Goldsmiths, University of London. In her works on paper as well as in her spatial installations, she follows the principles of collage. In 2016 the Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf and the Kunstmuseum Luzern both hosted a solo exhibition of her works. Additional solo exhibitions at the Kunstmuseum Bonn and the Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig are following in 2018. Currently, Frauke Dannert holds the Dorothea-Erxleben scholarship and teaches at the Braunschweig University of Arts. She lives and works in Cologne.

In her second solo exhibition at Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer, Frauke Dannert transfers her constructional and analytical strategies of collage from architecture to plant life. The title ‘folie’—the French term for a formally thought through, but otherwise useless building in garden architecture—refers, as regards content, to Dannert’s emblematic architectural collages. Phonetically the term simultaneously adds new clusters of visual motifs to her work: works on paper, photographs and a mural are dedicated to elements from the field of botany, such as the leaves (ital.: foglia / fr.: feuille) of a tree or a plant.

Made into a collage of crystalline growth, the now multiplied individual motifs of ‘Splitter’—slivers— (2016) and Dolde—umbel—(2016) still show the architectural motifs that are characteristic of Dannert’s work, as, for instance, the light wells of Le Corbusier with their basic deltoid shape. The serial elements, that were conceived and made by humans, follow time-based aesthetic ideas and underlie the mathematical principles of geometry, may initially appear paradoxical, juxtaposed with their own trailing growths. But they might also conjure up images of crystals and rocks like pyrite which combine geometric shapes with living growth: Algorithms of natural phenomena or the chromosomal formulae of the genetic make-up of humans, animals or plants spring to one’s mind—and therewith the intertwinement of mathematical formula and natural processes.

In Frauke Dannert’s black and white multi-exposures from the series ‘Orangerie’ (2017), architectures of modernistic garden buildings are interlaced with the amorphous structures of various leaves and grasses and form a rhizomorphic growth of steel, glass and cellulose. Due to the reflections and superimpositions of clear lines and grids, the spatial laws dissolve in a kaleidoscopic manner. The engineer’s traditional pursuit of statics is confronted with an autonomous process of change that manifests itself in the nature of the incorporated flora.

The artist’s interest in the interlacement of interior and exterior space continues with the inclusion of motifs from garden architecture and conservatories in her (photographic) collages. The disintegration of static architectural structures by way of light and transparency and their dynamization through deconstruction that also underlie Dannert’s installations with overhead projectors are here concentrated on the planar square of the photographic paper.

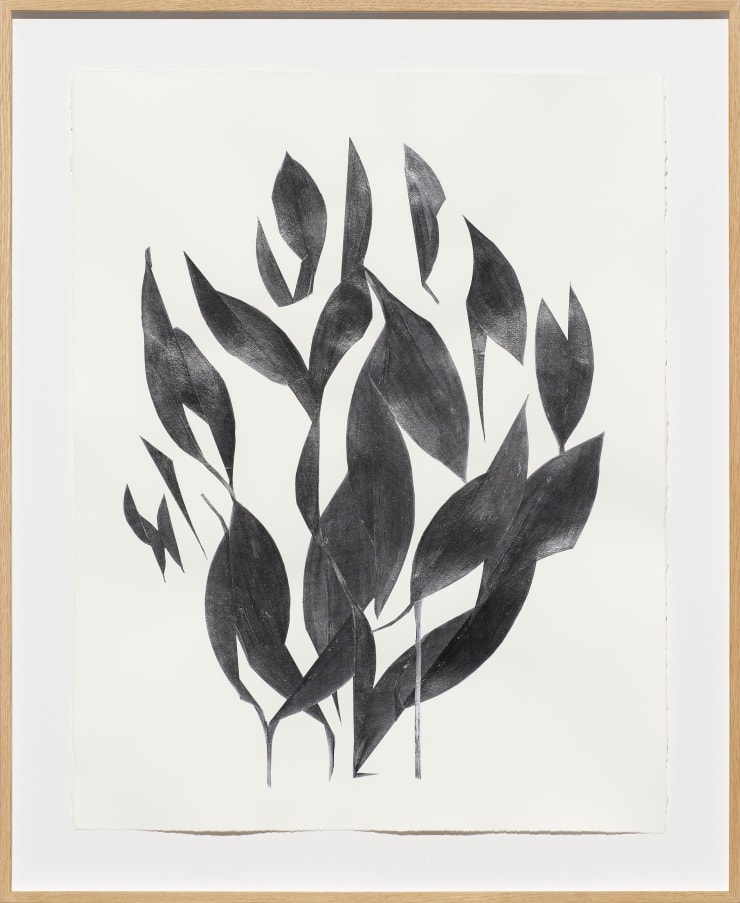

Scans of plant leaves constitute the starting point of the paper collages from 2017 and 2018. In an interplay with partial cut-outs and varnishing, they become the object of a playful as well as an explorative approach to the simple amorphous shaping and the complex surface structure of the leaf. While some of the works appear to follow the flat arrangements of ‘naïve’ plant classification or scientific displays, similar to Dannert’s ‘Templates’, the artist reverts with her botanical motifs to the strategies of building and construction.

Motifs from brutalist architecture, photocopied and collaged into fantasy buildings, are now being replaced by detailed images of delicately veined plant leaves, which obsoletely, and sometimes perpetually, assemble again into a leaf, a tree, a plant or branches. The proportionally skewed causality of a ‘constructed nature’ allows the delicate stems to turn into pillars and columns, trunks and connecting grids, which carry canopies and treetops, support their own bodies and elevate the rea- listic motifs into surreal constellations.

Hence the meticulously coordinated pieces of the leaf collage ‘Bosco’ (2018) conjure up an empirically unlikely, if impossible, botanical growth. The delicate veins and the sprawling arms of the ‘Banderole’ add an animalistic quality to the motifs, while the basic shapes of the collage remain pervaded by an open symbolism.

The ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss used the term ‘bricolage’ to describe the nature of ‘primitive’ building and organization with ‘remains of previous constructions and destructions’ which often reflect the mythical thought of indigenous populations: ‘Each element represents a set of actual and possible relations’. Thus, the elements are not only to be defined by their potential use for construc- tion, but they refer to other worlds, beyond themselves, through the evidence their ‘former’ lives have left behind.¹

Whereas the architecture in Frauke Dannert’s collages immediately evokes historico-cultural classi- fication and reflection, the plant motifs appear to virtually evade any chronological and contextual connection. The concreteness, immanent to the building per se, opens up to the universality of nature. Yet a mythical quality becomes apparent in the exhibition ‘folie’—and it appears to go far beyond the eventfulness of civilization.

Jari Ortwig | Translation by Susanna Fahle

¹Cf. Claudia Lévi-Strauss: Die Wissenschaft vom Konkreten, In: Das wilde Denken, 1973 Frankfurt a.M., P 30 et seq.

FRAUKE DANNERT folie [fɔli]

Preview: 22. März 2018, 19:00

Frauke Dannert (b.1979 in Herdecke, DE) studierte an der Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf und am Goldsmiths College in London. In ihren Papierarbeiten und räumlichen Installationen arbeitet sie mit dem Prinzip der Collage. 2016 richtete ihr das Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf und das Kunstmuseum Luzern eine Einzelausstellung aus. Weitere Solopräsentationen im Kunstmuseum Bonn und im Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig folgen 2018. Aktuell ist Frauke Dannert Dorothea-Erxleben-Stipendiatin und unterrichtet an der HBK Braunschweig. Die Künstlerin lebt und arbeitet in Köln.

In ihrer zweiten Einzelausstellung in der Galerie Lisa Kandlhofer überführt Frauke Dannert ihre konstruktiven wie auch analytischen Strategien der Collage von der Architektur in die Pflanzenwelt. Der Titel „folie“ – der als französischer Fachbegriff in der Gartenarchitektur ein formal durchdachtes jedoch zweckloses Gebäude bezeichnet – nimmt inhaltlich Bezug auf Dannerts emblematische Architekturcollagen. Lautsprachlich spannt der Begriff zugleich den Bogen zu einer neuen Bildmotivik in ihren Werken: Papierarbeiten, Fotografien und eine Wandmalerei widmen sich Elementen der Botanik, wie etwa dem Baum- und Pflanzenblatt (ital.: foglia / franz.: feuille).

Collagiert zu kristallinen Gewächsen zeigen die vervielfachten Einzelmotive in „Splitter“ (2016) und Dolde (2016) noch die für Dannerts Werke typischen Architekturmotive, wie etwa die Lichtschächte von Le Corbusier in der Grundform eines Deltoiden. Die seriellen, vom Menschen erdachten und erbauten Elemente, die zeitbasierten ästhetischen Vorstellungen folgen und mathematische Prinzipien der Geometrie zugrunde liegen, stehen ihrer eigenen rankenden Ausbreitung zunächst paradox gegenüber. Doch werden womöglich Bilder von Kristallen und Gesteinen wie Pyrite wachgerufen, die geometrische Form und lebendiges Wachstum in sich vereinen; Algorithmen innerhalb der Naturereignisse oder chromosomische Formeln des menschlichen, tierischen und pflanzlichen Erbgutes kommen in den Sinn – und damit das Ineinandergreifen mathematischer Formeln und natürlicher Prozesse.

In Frauke Dannerts mehrfachbelichteten Schwarzweiß-Fotografien der Serie „Orangerie“ verschränken sich Architekturen modernistischer Gartenbauten mit den amorphen Strukturen verschiedener Blätter und Gräser zu einem rizomatischen Geäst aus Stahl, Glas und Cellulose. Räumliche Gesetzmäßigkeiten lösen sich kaleidoskopartig durch Spiegelungen und Überlagerungen klarer Linien und Raster auf. Dem klassischen Ingenieursstreben nach Statik und Ordnung wird ein autonomer Veränderungsprozess entgegengesetzt, der sich im Wesen der eingebundenen Pflanzen manifestiert. Mit der motivischen Einbeziehung von Gartenarchitekturen und Gewächshäusern in ihre (fotografischen) Collagen setzt sich das Interesse der Künstlerin an der Verschränkung von Innen- und Außenraum fort. Die Auflösung architektonisch-statischer Strukturen durch Licht und Transparenz und ihre Dynamisierung durch ihre Dekonstruktion, wie sie etwa Dannerts Rauminstallationen mit Overheadprojektoren zugrunde liegen, konzentrieren sich hier auf dem flächigen Quadrat des Fotopapiers.

Scans von Pflanzenblättern bilden den Ausgangspunkt der Papiercollagen von 2017 und 2018. Im Zusammenspiel mit partiellen Cutouts und Lackierungen werden sie zum Gegenstand einer spielerisch-forschende Annäherung an die einfache amorphe Formgebung und die komplexe Oberflächenstruktur des Blattes.

Während einige der Werke durch die flächige Anordnung der Motive die Prinzipien „naiver“ Klassifikationen von Pflanzen oder naturwissenschaftlicher Schautafeln aufzunehmen scheinen, ähnlich wie in Dannerts „Templates“, kommt die Künstlerin innerhalb ihrer botanischen Motivwelt auch auf die Strategien des Bauens und Konstruierens zurück.

Anstelle brutalistischer Architekturmotive, die als Fotokopien zu neuen Fantasiebauten collagiert wurden, treten nun die detaillierten Abbilder fein geäderte Pflanzenblätter, die sich obsolet und vereinzelt perpetuell wiederum als Blatt, Baum, Pflanze oder Geäst zusammensetzen. Die verschobenen proportionalen Kausalitäten der „gebauten Natur“ lassen die feinen Stengel zu Säulen und Pfeilern, Baumstämmen und verbindenden Rastern werden, welche Laubdächer und Kronen tragen, ihre eigenen Körper stützen und die realistischen Bildmotive in surreale Konstellationen überhöhen. So assoziieren beispielsweise die genau aufeinander abgestimmten Passstücke der Blättercollage „Bosco“ (2018) ein pflanzliches Wachstum, das erfahrungsgemäß unwahrscheinlich, ja unmöglich ist. Die feinen Adern und die auslaufenden Arme der „Bandarole“ lassen die Motivik ins Kreatürliche fließen während die Grundform der Collage einer offenen Symbolik verhaftet bleibt.

Mit dem Terminus „bricolage“ bezeichnete der Ethnologe Claude Lévi-Strauss das Wesen des „primitiven“ Bauens und Ordnens mit „Überbleibseln von früheren Konstruktionen und Dekonstruktionen“, in dem sich das mythische Denken der Naturvölker oftmals widerspiegelt: „Jedes Element stellt eine Gesamtheit von konkreten und zugleich möglichen Beziehungen dar“. So werden die Bauelemente nicht nur in ihrer Qualität als nützliches Material bewertet, sondern verweisen über sich selbst hinaus auf Welten, die ihnen durch ihre „früheren“ Leben bereits eingeschrieben sind.¹

Während Architektur in Frauke Dannerts Collagen eine kulturgeschichtliche Einordnung und ihre Reflexion unmittelbar evoziert, scheint sich die Motivik der Pflanzen hier einer zeitlichen Anbindung und Kontextualisierung quasi zu entziehen. Die Konkretheit, welche dem Bauwerk per se innewohnt, öffnet sich in eine Universalität der Natur. Dennoch kommt in der Ausstellung „Folie“ eine mythische Qualität zum Tragen – diese jedoch scheint über eine zivilisatorische Ereignishaftigkeit

weit hinauszugehen.

Jari Ortwig

¹Vgl. Claudia Lévi-Strauss: Die Wissenschaft vom Konkreten, In: Das wilde Denken, 1973 Frankfurt a.M., S. 30f.

![Frauke Dannert | Folie [fɔli]](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_920,h_920,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-lisabird/usr/images/exhibitions/group_images_override/58/frauke-dannert-no1.-neu.jpg)